French Louis XVI Pendule with biscuit and porcelaine de Sèvres

French Louis XVI Pendule with biscuit and porcelaine de Sèvres

Signed: Charles du Tertre [on the dial] (before 1778)

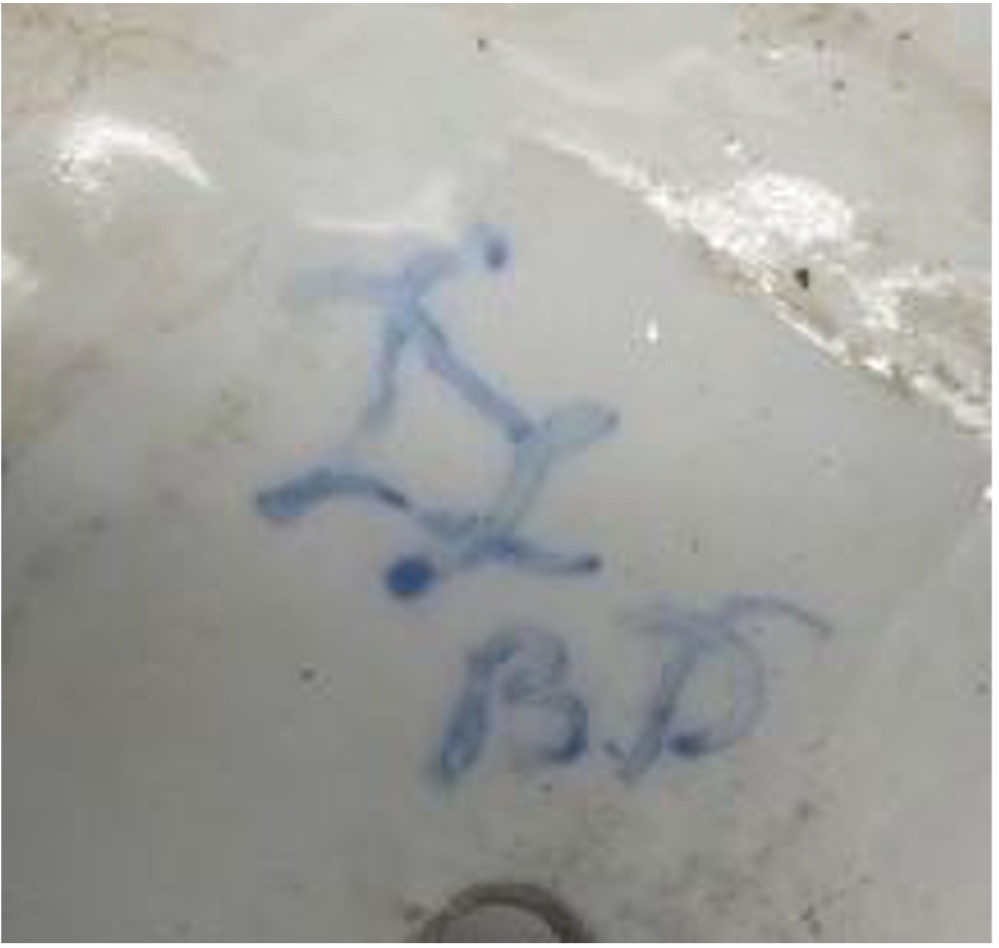

Marked: Blue double L for Sevres and BD for Francois Baudouin the Elder, mainly active as gilder at the ‘Manufacture de Sevres’ between 1750 and 1800 (vase and column)

La petite tendresse: Carved into the clay: B, signature of Jean Jacques Bachelier, director of the sculpture workshop between 1766 and 1773.

Designed by Simon-Philippe Poirier (c. 1720 – 1786) and Dominique Daguerre (c. 1740 – 1796)

The eight-day movement has an eight-day going movement and strikes the half- and full hours on a bell. Two asymmetrically positioned winding holes. The hours are indicated by Roman numerals, the minutes by Arabic numerals. The clock is signed Charles dy Tertre A Paris on the backplate of the movement and on the dial.

Freely translated from the French after Jean-Dominique Augarde, 2023.

This mantel clock, of which only three copies are known, originating from the former collection of the Klokkenmuseum (Clock Museum) in Frederiksoord, the Netherlands, is part of a larger whole of mantle clocks which must be studied in its entirety.

At the beginning of the 1770s, the ‘Manufacture Royale de Sèvres’ was already producing mantle clocks entirely in porcelain or with porcelain plaques in very small numbers.

In 1771 they introduced a neo-classical design, consisting of a half column topped by a vase. This was a model fashionable at the time, which may have been inspired by an earlier design by Robert Osmond (1711-1789)i

Initially, Sèvres produced the column in 'Bleu nouveau' porcelain, also known as 'Bleu du Roy' or ‘Beau Bleu’, a model with gold-trimmed white ‘cannelures’-grooves, with a vase with gold decorations. A few years later, the column was also made in ‘Bleu Celeste’ and ‘Vert’, for the models without a vase or the third model.

The sales records of the Manufacture de Sèvres mention “Columns for mantle clocks” for the first time in 1772. But among the new models of the year 1770, a “vase on column I” and a “column of the already mentioned vase” were already presented.ii Between 1772 and 1791, at least 20 or 21 “columns for clocks” were sold. Almost all of these were purchased by the marchands-merciers Simon-Philippe Poirier (c. 1720-1786) and Dominique Daguerre (c. 1740-1796).

In the various records of Sèvres, one regularly finds the general term “Vase mantle clock”. For example, the clock maker Dubois – apparently Germain Dubois (1733 – before 1806) – bought a vase mantel clock in the colour ‘Beau bleu’ on the first of December 1775 for the sum of 96 Livres.iii

The different models

In any case, three different models have been designed based on the half column. The mantle clock described here is an example of the second design.

Poirier and Daguerre, who acquired most of most of the columns, were responsible for the gilt bronze mounts. They chose the bronze casters and commissioned the various bases and ornaments. Similarly, Poirier and Daguerre chose the craftsmen who made the clockworks. From 1771 onwards, Charles Du Tertre became their main supplier, which he remained until his death in 1778.iv

The first model is designed as a separate column with a vase as crowning ornament. In the subsequent models, the half column forms the central element of a larger composition. These separate variants were developed almost simultaneously.

The first model

The column is placed on a chiseled and gilt bronze base adorned with a branch and leaf motifs, produced by Poirier and Daguerre. Some examples have a second marble plinth. The dial is framed by a bronze chiselled rim and the vase is decorated with oak leaves, garlands and a pine cone.v

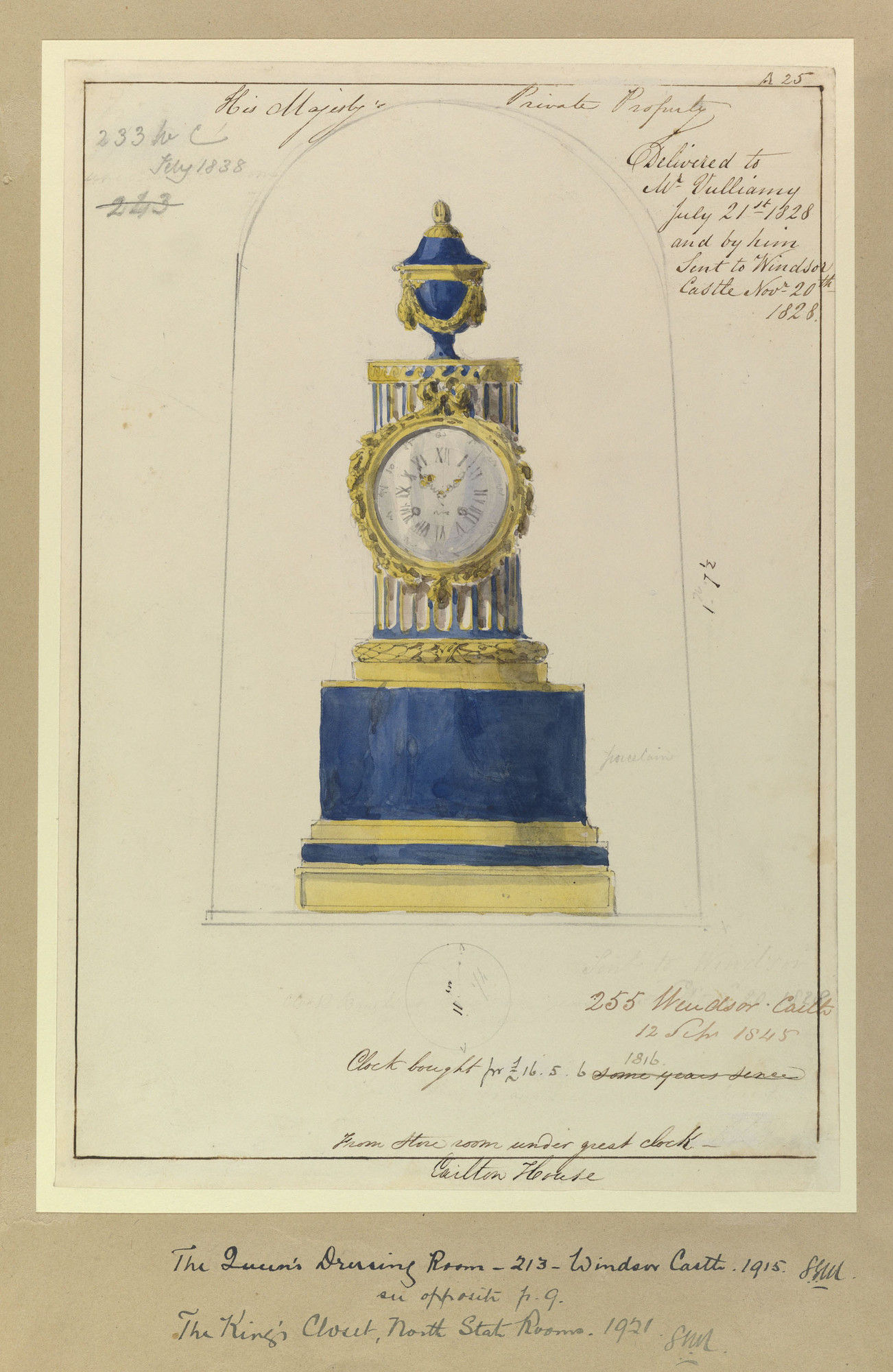

An example of the single column on a round base in blue porcelain was bought by George IV of England and at present still remains in the British Royal Collections.vi The original clockwork of this example was made by Charles Du Tertre (see ill. 1).

Another example, also with a Du Tertre clockwork, belonged to Duke Charles-Alexandre de Lorraine (1712-1780), Governor of the Southern Netherlands. The Prince had a medallion with the portrait of his niece, Queen Marie-Antoinette, placed on the column:

“A mantle clock by Charles Du Tertre, Paris; A week clockwork with striking mechanism; The porcelain case in the shape of a column by Sèvres, carrying a small vase, with the portrait of the Queen of France underneath; the whole decorated with gilded bronze”.vii

An example of a variant by Germain Dubois from 1786viii can be found in the Wallace Collection and in the former collection of William Redford.ix In the latter, the garland is composed of flowers and fruit (see ill. 2).

The third model

The third model, which does not feature the small vase, consists of a column on which an allegorical female figure rests on the left side. The figure symbolizes Friendship and carries two hearts in one hand and a medallion in the other, which rests on the column. On the right side of the column, a putto plays with a dog, which symbolizes Fidelity and Loyalty.

This model, of which most were made around 1780, is sometimes executed in the color “Bleu Celeste”x and sometimes in “Vert”xi. The original sketch is kept in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and was probably presented as a proposal to the Duke of Saxe-Teschen and his wife, Archduchess Marie-Christine, sister of Marie-Antoinette, thesuccessors to Charles de Lorraine, in Brussels.xii

At present one example can be seen in the Palace of Versailles.xiii This mantel clock with a sky-blue background and a clockwork by Charles Du Tertre, was delivered by Poirier and Daguerre on 3 March 1777xiv to the Comte d'Artois, the later Charles X (1757-1836), for the Palais du Temple in Paris.

The actress Marie-Josèphe Laguerre (1754-1783) had one in her possession as well. Her mantel clock was fitted with an Ageron clockwork:

“Strikes the hour and half hour, in the grooved porcelain Sèvres stem of the column on which a female figure leans. She has a medallion with a miniature in her hand”xv

Possibly this is the example, executed on a green ground, that is presently kept in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (see ill. 3).xvi

Such a mantel clock, signed ‘Sotiau à Paris’, was also described in the inventory of 1806:

“(…) on the mantelpiece of the “salon en suite du salon de musique” of the residence of the Marquise of Montesson (1738-1806), wife and widow of the Duc d'Orleans (1725-1785); A clock signed Sotiau à Paris, with striking mechanism, on white marble base, and painted porcelain column, with figure and painted medallion, and gilded copper ornament (…)”.xvii

Four examples by Sotiau are known to date: one more in the color 'Bleu Celeste' in the Walters Arts Gallery at Baltimore xviii, and another in the color 'Vert' in the collection of Charles III, King of Great Britain.xix Finally, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York owns a blue ground piece with a clockwork by Charles Du Tertre, which lacks the medallion.xx

The second model: the mantle clock with column, flanked by figures

We will now take a closer look at the most rare model. Only three authentic examples, including two with Du Tertre clockworks, all kept in private collections, are known to date: The present one, a second in the Dimitri Mavrommatisxi collection, and a third offered for auction in Paris in 1968.xxii

The mantle clock is constructed as follows: the base is formed by a double plinth, on which the column is placed in the middle foreground, flanged by two Sèvres biscuit porcelain figures. In the background two obelisks crowned with flames and decorated wreaths and trophies in gilded bronze are placed.

Unlike the Mavrommatis-model, described by John Whitehead, the bronze lunette for the dial is decorated with coin motifs.

A second plagiarised example, modeled around an authentic Sèvres column, probably made by Germain Dubois. However, the original mantel clocks made by Poirier and Daguerre are easy to be distinguish from this.

Only one example of this copy is known.xxiii It differs in the shape of the plinth, the gold base of the column and the floral garland on the vase. In addition, the obelisks are slightly smaller, and they are crowned with spheres instead of flames.

The pieces by Poirier and Daguerre are decorated with two biscuit porcelain figures of “Paris, prepared to give the apple, the prize of beauty”, from 1770, based on the sculpture design by Nicolas Francois Gillet (1709-1791) from 1757) and with “La Petite Tendresse” a design from 1769 by an unknown maker. Both figures are part of the surtout, which was made by Sèvres in honour of the marriage of the Dauphin, the later Louis XVI, in May 1770.xxiv

The mark of the gilder, Francois Baudoin, can be found on the vase and the column (see ill. 4).

The “Petite Tendresse” on the present mantel clock is carved with the letter ‘B’, for Jean-Jacques Bachelier (1724-1806) (see ill. 5). He led the sculpture workshop of Sèvres from 1767 to 1773. The date 1773 is therefore the terminus ante quem, or the earliest possible date for the production of this mantel clock.

Madame Du Barry

It has been established that on December 27, 1771, Poirier and Daguerre sold a “column mantle clock with porcelain figures” to the Comtesse du Barry for the sum of 2112 livres.xxv Although the column for the mantle clock was only registered in 1772 with the Manufacture de Sèvres and although the figures are said to be made of porcelain and not of biscuit or biscuit porcelain, the present piece can arguably be identified as the recorded example.xxvi

On 12 floreal an II (the 1st of May 1794) such a mantle clock was confiscated from the Comte de Provence (the later Louis XVIII) in the Palais du Petit Luxembourg:

“Another mantel clock on a base of fire-gilt bronze with a flattened column of blue, white and gold porcelain on which the dial is mounted, with a lidded vase as top decoration. Standing figures on both sides in Sèvres biscuit, behind them two obelisks made of white marble, decorated with trophies, garlands, wreaths and torches.”xxvii

It has been suggested that on the basis of this description, without mention of a signature, the mantle clock of the Dimitri Mavrommatis collection (see ill. 6) could be identified as Madame Du Barry's mantle clock.xxviii Due to the absence of a signature, it is supposed that this mantel clock could also have been the example of the Comte de Provence.xxix

Since there seems to be no trace of Madame Du Barry's mantle clock, it has been assumed that the King's mistress gave the clock to the young prince or his wife, Marie-Josephe de Savoie, in 1772.

This hypothesis is highly questionable for two reasons: Firstly, nothing can prove that Madame Du Barry would have given gifts to the grandchildren of Louis XV, because of their certain animosity towards her. Secondly, the lady of the castle of Louvecienne was immensely wealthy thanks to the generosity of her lover, which amounted to the vast sum of 2,700,000 livres at the death of the king.xxx One might think that the value of the offered mantle clock (of 2112 livres) was a rather cheap gift for a prince, while she radiated wealth and splendour.

Brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt bluntly write in their biography of Madame du Barry:

“The life of Madame du Barry (…) is an insane dream of a gallant woman, a frenzy of expense, an extravagance of luxury; millions spent on fads, millions on rare jewels, (…) silk, velvet; millions to what is most immensely expensive; a tidal wave of money, the royal treasury poured out upon tailors, milliners, seamstresses, etc. In this wondrous inventory of so many wonders, in these heydays of expenditure, as if they were tuned by Cleopatra's steward, the cost and the detail, as pearls melted by a woman's fantasies. The infinity of precious metals; the silver, the gold, on with which her table boasts, and with which her dress is adorned.”xxxi

It is therefore most likely that the mantel clock seized in 1794 was simply bought by the Comte or the Comtesse de Provence, due to their great passion for the products of the Manufacture de Sèvres,

The letter B, which was misidentified in the nineteenth century, leads us to recognize another similar mantle clock then the present one in the collection of the son of the famous writer Alexandre Dumas (1824-1895):

“Mantle clock from the Louis XVI period, in soft Sèvres porcelain, gilded bronze and white marble: The movement is set in the stem of a fluted column, topped by a vase with garlands. On both sides a small obelisk with bronze attributes. On the beautifully shaped base are two figurines in Sèvres biscuit: A Nymph and Paris with an apple in his hand.” xxxii

Conclusion

The present mantle clock, of which only three examples are known, testifies to the extreme refinement for which the most beautiful compositions from the second half of the eighteenth century are known.

It should be emphasised that of the three examples, the present mantel clock is the best preserved one and is unquestionably kept in an exceptional condition.xxxiii Not only does it have its original dial on which the name of Charles Du Tertre can be read (until 1778 the official clockmaker from Poirier and Daguerre), but also the fire-gilt and very finely chiselled bronze testify to an excellent quality and artistry.

It is therefore quite possible that this mantle clock comes from Madame du Barry or from the Comtesse de Provence. Whichever it may be, this mantel clock is the epitome of late eighteenth-century sophistication, with a provenance that can be regarded as Royal by any measure.

Literature:

Augarde, Jean-Dominique, Les Ouvriers du Temps, La pendule de Louis XIV à Napoléon Ier, Genève, Antiquorum, 1996.

Bastien, Vincent, « Simon-Philippe Poirier (vers 1720-1785) », in La Fabrique di Luxe, Les marchands merciers parisiens au XVIIIème siècle, Paris, Paris-Musées, 2018.

Bastien, Vincent, « De Versailles à Paris : la collection de porcelaines du comte et de la comtesse de Provence », Versalia, n° 25, 2020, pp. 71-88.

Baulez, Christian, Madame du Barry de Versailles à Louveciennes, Marly,, Musée-Promenade de Marlyle-Roi, 1992.

Baulez, Christian, « Marie Josèphe Laguerre, diva et collectionneuse », L’Objet d’Art, n°416, 2006, pp. 118-130.

Bellaigue, Geoffrey de, French Porcelain in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen, London The Royal Collection, Enterprises Ltd, 2009.

Ennès, Pierre, « Le surtout de mariage en porcelaine de Sèvres du Dauphin, 1769-1770 », Revue de l'Art, 1987, n°76. pp. 63-73.

Goncourt, Edmond et Jules, La du Barry, Paris, Editions Payot & Rivages, 2018.

Hughes, Peter, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Furniture, Londres, The Trustees of the Wallace Collection, Londres, 1996, tome I pp.

Hugues, Peter, French Eighteenth-Century French Clocks and Barometers in the Wallace Collection, Londres, 1994.

Munger, Jeffrey & al., The Forsyth Wickes Collection in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 1992.

Ottomeyer, Hans et Pröschel, Peter, Vergoldete Bronzen, Die Bronzearbeiten des Spätbarocks und Klassizismus, Munich, 1986.

Pinot de Villechenon, Marie-Noëlle, & al ; Falconet à Sèvres ou l’art de plaire, 1757-1766, Paris, RMN, 2001.

Préaud, Tamara, Scherf, Guilhem, La Manufacture des Lumières, La sculpture à Sèvres de Louis XV à la Révolution, Dijon, Editions Faton, 2015.

Savill, Rosalind, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Sevres Porcelain, Londres, The Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1988.

Watson, F.J.B., Wallace Collection, Furniture; Londres, The Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 1956.

Whitehead, John, Sèvres sous Louis XVI, le premier apogée, Paris, Éditions courtes et longues, 2010

Notes.

i One expamle is part of the Swedish Royal collections. At the same time, Osmond designed a larger version in which the vase is flanked by two putti. These putti symbolize geometry and literature. See, for example, Augarde 1996, p.25;

ii 2 Savill, 1988;

iii Ibidem;

iv Augarde 1996, p. 311;

v Sale, Paris, Ader, Picard, Tajan, 12 December 1990, n°105, dial and clockwork by Charles Du Tertre;

vi Bellaigue 2003, n°281;

vii Auction, Brussels, 21 May 1781 and following days;

viii Watson 1956 ; Savill 1988 ; Hughes 1994 ; Hughes 1997;

ix Sale, London, Christie's, 9 June 1994, n°3;

x For example, Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. 39.41.58, and Musée national du château de Versailles, VMB 889;

xi For example, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 65. 2236, and Bellaigue 2003, n°281;

xii Inv. 60.692.7;

xiii VMB 889;

xiv Bastien 2020;

xv Sale, Paris, 10 avril 1782, n°28, et Baulez 2006 ;

xvi Munger & al 1992, n°314;

xvii ANF,MC, LXXVIII, 1073, 12 February 1806, inventory after death;

xviii Inv. 58.249;

xix Bellaigue 2003, vol. III, n°282;

xx Inv. 43.163.24 a and b;

xxi Whitehead 2010, p.23. The dial is anonymous, the clockwork is by Charles Du Tertre and the number ring is devoid of an ornament, unlike the other two;

xxii Sale eiling, Paris, Rheims, Guilloux, Buffetaud, 28 March 1968;

xxiii Auction, London, Sotheby's, 8 July 1983, n°122, and Augarde 1996. The porcelain vase is missing and the female figure is likely a replacement, as she is looking in the same direction as Paris;

xxiv Ennès 1987;

xxv Savill 1988;

xxvi Ibidem;

xxvii ANF, Maison du l’Empereur, O2 470;

xxviii Bastien 2018, p.92;

xxix Bastien 2020;

xxx Baulez 1992;

xxxi Goncourt 2018;

xxxii Estate of Alexandre Dumas, auction Paris, 2 March 1896, n° 184;

xxxiii The pedestal of the vase was once broken and shows an old repair

- Provenance

- Possibly the Comtesse du Barry (1743-1793) or the Comte de Provence (1755-1824;

Klokkenmuseum, Frederiksoord, the Netherlands - Period

- ca. 1771-1773

- Material

- porcelain and biscuit de Sèvres, white marble, chiseled and gilded bronze

- Signature

- Charles du Tertre

- Dimensions

- 37 x 27.5 x 19 cm

Global shipping available